A previous article on this blog told the story of Keith Jarrett’s trio in the years 1967-1972 with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian. The later part of that story included recordings by the trio with tenor sax player Dewey Redman on the album Expectations. We pick up the story after the release of that album, when Redman formally joined the band, making it a quartet – widely known as Keith Jarrett’s American Quartet.

In 1972, shortly after the release of Expectations, Columbia Records dropped Keith Jarrett, freeing him up to sign with Impulse! Records, the jazz subsidiary of ABC. The label was famous for its recordings of John Coltrane in the 1960s, and during the late 1960s and early 1970s was still connected to Coltrane with posthumous releases of his music and recordings by musicians associated with him, including Pharoah Sanders, Alice Coltrane and Archie Shepp. By the end of 1972 these musicians moved elsewhere and Impulse was looking for new talent.

In a brilliant move by Jarrett’s manager George Avakian, the contract with Impulse included an ‘exceptions from exclusivity’ clause that allowed the pianist to release various types of projects on other labels. The contract read: “Keith would be permitted to finish his current ‘serious music’ album for ECM (most of it music he composed under Guggenheim Fellowship), but he may want to do similar recordings during the term of his ABC contract.” That ‘serious’ recording was released on ECM Records as the double album In The Light, featuring compositions for strings, brass, guitar, piano and percussion. The clause enabled Jarrett to have a dual recording career throughout the life of the American quartet, recording solo piano albums and other projects on the ECM label.

The American group booked two week-long engagements at the Village Vanguard in New York in January and February of 1973. The second of them yielded the first album for Impulse! and the band’s only live recording for the label. The club was a favorite live recording venue for many jazz artists over the years. Despite its odd shape of a narrow room with low ceilings it had great acoustics, captured on many classic recordings by Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, John Coltrane and others.

The band is in top form on this album, especially on the long title track Fort Yawuh that demonstrates the band’s ability to move seamlessly between different musical styles and moods. Dewey Redman showcases the Chinese Mussete midway through the track, and some of you may also notice the inconspicuous sound of a triangle. This brings us to the topic of a fifth credit on that album, that of Danny Johnson on percussion. Who was Danny Johnson, you ask? Charlie Haden provides the answer: “Danny Johnson is a great, great painter, and a great friend, and someone who was at EVERY gig, and one day he suddenly asked to sit in with us at the Village Vanguard. Keith asked, ‘What do you play?’ ‘Triangle!’ said Danny Johnson. Keith said yes and Danny came down with a big oriental rug and sat like a sitar player with his triangle. And that was the night we recorded Fort Yawuh.” The painter, a friend of jazz artists including Charles Lloyd, Keith Jarrett’s former employer, will make additional appearances on the quartet’s recordings, and also on an album by Dewey Redman in 1973.

At this point Keith Jarrett established a touring and recording double life, alternating between his work with the quartet and solo piano. A month after recording Fort Yawuh he recorded a series of improvised piano solo recitals in Germany, released on the ECM label as the three-LP set Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne. Later in the year the quartet played a number of venues in the US as part of a package tour organized by Impulse, featuring its roster of artists including Gato Barbieri, Paroah Sanders and Alice Coltrane. A recording by the quartet is included in the album Impulse Artists On Tour, released in 1974.

In November of 1973 the quartet played a number of concerts in Europe, including a rare performance captured on film in Berlin, Germany during the Berliner Jazztage (Berlin Jazz Days) festival, later known as Jazzfest Berlin. At this point they were joined by a bonafide percussionist, Guilherme Franco, who previously recorded with McCoy Tyner and Archie Shepp. Here is a different version of Fort Yawuh recorded as a quintet on this event:

The quartet travelled to Japan at the beginning of 1974 to play venues in major cities, and in February that year recorded their first studio album for Impulse. Joined by Guilherme Franco, Treasure Island was recorded over two days. The title track features Sam Brown on guitar, a melodic tune that was played by Keith Jarrett as an encore on some of his solo concerts in 1975.

A favorite track from that album is Fullsuvollivus (Fools Of All Of Us), a great ensemble piece with fine solos by Jarrett and Redman. And of course, that bell by Danny Johnson.

The quartet performed regularly in 1974, with many shows taking place on the US West and East coasts and in Canada. In October of that year they went into the recording studio again, and in two days cut enough material for two albums. The first to be released from these sessions was Backhand, a lesser known album in the band’s discography. It was released on CD only in Japan, and finally was included in the boxset Keith Jarrett The Impulse Years 1973-1974.

The following album, Death and the Flower, is one of the highlights in the band’s discography. The sidelong title track finds the pianist also playing flute and osi drum (a form of tuned wood tongue drum).

Pianist Kenny Werner picked this track when reviewing the music of Keith Jarrett for JazzTimes: “The band of Redman, Haden, Motian and percussionist Guilherme Franco was my favorite throughout much of the ’70s. They play rhythm and sounds for a full six minutes before going into the most heart achingly beautiful ballad, Death and the Flower. They then move into a raw groove in which Redman re-interprets the changes. As with much of Jarrett’s composition and style of playing, it captured my heart in a way that no one else could.”

Time to introduce the producer on the albums the quartet recorded for Impulse in 1973 and 1974, Ed Michel. Spending his early career in the west coast, he learned the art of music production at the Pacific Jazz label. He later moved to NYC and became assistant to producer Orrin Keepnews at Riverside Records. He joined ABC, Impulse’s parent company, in 1969 and produced many albums for the label until his departure in early 1975. Talking about recording the quartet he said: “Keith is one of the guys who is a pleasure to record. He always knew what he wanted to do and it was a working band made up of brilliant players. It was a band where almost any take was good enough.”

The session that yielded Death and the Flower was one of his last for the label. He recalls the session and one particular track on it: “There’s one tune that he does—it’s a duo with Charlie Haden— ‘Prayer.’ They played it, and I thought, ‘Jesus, that’s good.’ Keith said, ‘Let’s do another one.’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ They did another one. Keith played an even better solo, and then it broke down. It just stopped at about five minutes. And I said, ‘Well, we’ve got the first one. There’s no problem. Why not do one more just for the hell of it because it’s going so well?’ The third one was the take. When I’m teaching a production class, sometimes I do that at schools, I’ll play that as an indicator of ‘Don’t stop just because it’s good.’”

Here is Prayer, a duo featuring Jarrett and Haden, one of the most melodic and melancholic pieces in Keith Jarrett’s repertoire:

One thing that came with that band was very strong personalities, no easy task for the band leader to cope with. Keith Jarrett had the utmost appreciation for the musical gifts of his band members but he had to find a way to write for them: “There had to be a way to have Dewey not play on changes, to have Charlie not play vamps forever (Although, when he wanted to play a vamp, there was nobody that plays them better than Charlie). But Charlie always wanted to challenge the tonic, and challenge the chord he’s playing. He’s not always going to play the root. ‘I’m sorry, I’m not gonna play that damn root. I don’t care what you think.’ And then every now and then, he’d play the root so beautifully that you’d just say, well, these are choices he’s making, I’m not gonna screw with this.”

But the music benefitted from these strong personalities in the group, as Jarrett was well aware of: “Charlie doesn’t rely on someone else’s ideas of what music is. He has his own. I’m obsessive, he’s obsessive, Paul’s obsessive. Those are the guys I want to play with. At the point where you are about to go insane is the point where the music starts to happen.”

1975 started with hectic activity of solo concerts for Keith Jarrett in Europe, famously yielding the iconic album The Köln Concert. Also of note is the recording of another favorite in his ECM catalogue, the album Arbour Zena with Jan Garbarek, Charlie Haden and a symphony orchestra. Over a year elapsed before the group entered a recording studio again, for a 3-day session in October 1975, and again they recorded enough material for two albums: Shades and Mysteries.

The opener to Shades is the track Shades of Jazz, demonstrating the band’s ability to swing with the best of them. But not for long, for the musicians’ tendency to embark on free-form improvisation takes the song into a different direction halfway through. Listening to this track years later, Paul Motian commented: “That’s happenin’ because of how we’re playing, we’re playing it from what Dewey’s playing. We start out swing time, and then the music starts to get apart from the swing time and goes in other directions, and then, as far as I’m concerned, just falls apart. And then we just start playing free.“

You will notice how high Paul Motian is in the mix on this tune. Jarrett commented about that aspect of their recordings on Impulse: “I loved it because I was also a drummer, so I knew what Paul was doing was so brilliantly correct for this situation that I was never gonna say a word about it. I couldn’t have ever imagined saying to Paul, ‘Paul, you’re playing too loud.’ Here was a guy who was probably waiting for this, through the whole brushes thing with Bill. Bill didn’t want him to use sticks.”

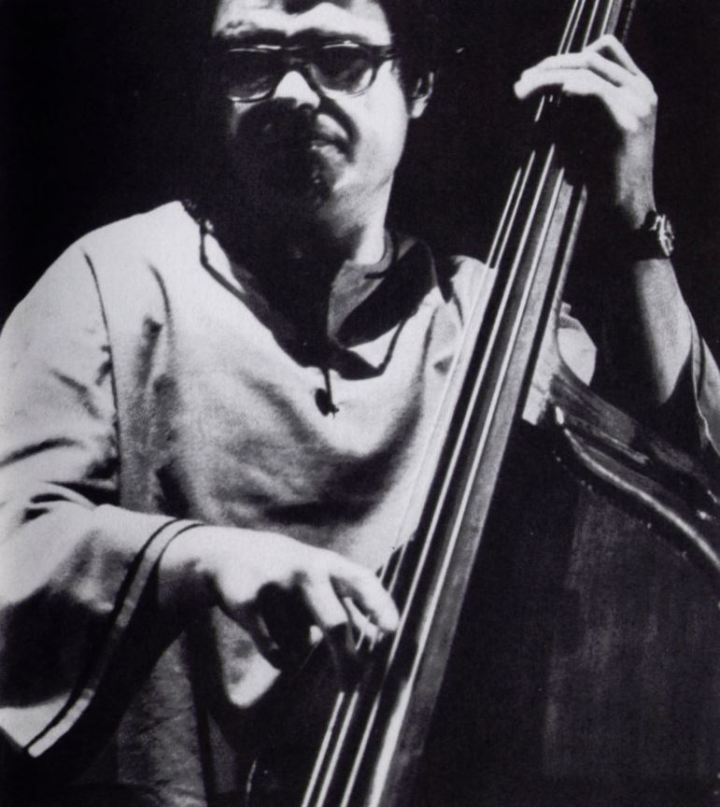

The album Mysteries features another great set of compositions by Keith Jarrett. Charlie Haden discussed the music Jarrett wrote for the band in an interview: “I do think that some of the greatest music made in that time period came out of that group. Keith was always his own person, with original ideas as a leader. Keith wrote specifically for us, first for the trio, and then the quartet. I loved it. He showed up at every rehearsal and soundcheck with new music. It’s amazing when you go over a new tune at a soundcheck and can’t wait to play it that night, since it already felt like ‘you.’ Especially the stuff from the Impulse years.”

A fantastic tune from the album is Everything That Lives Laments, starting with a prayer-like melody, followed by an interlude by Charlie Haden and then into the tune proper. Excellent solos by Dewey Redman here. Keith Jarrett reminisced about playing with Redman: “When he was on, he was definitely on. He was afraid that he was incompetent to play on chords. And one night, we’re playing one of my pieces, on which he never plays on the chords. And all of a sudden I’m noticing, wait, he’s playing on these chords, and not only is he playing on them, it’s like he’s done this for his whole life. It’s the only time it ever happened. And we came off the stage, and I said to Dewey, ‘What the hell… what was that, man!’ He said, ‘Well, Don Byas died today. I just felt Don’s spirit.’ Yeah. He played the shit out of the chords. He just played like he never had a problem with chords in his life.”

An interesting link between the ECM label and the quartet’s recordings for Impulse is sound engineer Tony May, Manfred Eicher’s go to engineer when an ECM recording was made in New York. Tony May engineered all of the Quartet’s recordings for Impulse, a total of 7 albums. Tony May’s engineering credits can be found on some of ECM’s best albums from the period, including Chick Corea’s first Return to Forever album, Dave Holland’s Conference of the Birds and John Abercrombie’s Timeless. He branched out of the jazz idiom to engineer many fantastic albums, including Van Morrison’s Moondance, recorded in 1969 and released in 1970. Keith Jarrett’s quartet next two albums were recorded for ECM, but not with Tony May as they were recorded in Europe.

We come to 1976, the most prolific one for the band as far as recording output, yet the most tumultuous as well. Sadly, at the end of that year the band disintegrated, but before we get to that point we have four more albums in front of us.

The first two were recorded for the ECM label and released after Keith Jarrett was off his contract with Impulse Records. In April of 1976 the band entered Tonstudio Bauer in Ludwigsburg and recorded the album The Survivor’s Suite. This is a unique album in the band’s output for a number of reasons. It is the only one the quartet recorded for ECM in a recording studio, benefiting from the legendary ECM sound.

The album lacks the frantic moments many of the group’s albums reach at times when it sounds as if each player is pulling into a different direction. The music sounds more composed throughout and performed at slow to medium speed. The album is split into two long pieces, each taking a full side of the LP. Here is a taste from the first piece Beginning:

In an interview with Stuart Nicholson in 2009 Jarrett told this story about the music that was written for the album: “The whole music of The Survivor’s Suite was written specifically for Avery Fisher Hall in New York, because I knew we were going to play there, I think it was opposite Monk as part of the festival (The quartet played that venue on July 3, 1975 in a shared bill with Oregon and Thelonious Monk’s quartet). I knew from playing in Avery Fisher Hall many times the sound was not precise enough onstage to play fast tempos, the sound got blurred – so I decided to write the music for that evening. So there was a rationale to that, but I think very few people would ever say, ‘Would you conceive, Mr. Jarrett, of writing for a specific hall?’ I probably would say, ‘No.’ But the answer lies in the fact that I knew the hall to be very poor for certain kinds of things and if you listen to The Survivor’s Suite you’ll notice there are no fast tempos.”

And a section from the second piece, Conclusion:

The band recorded one more album for ECM a month later, but this time it was a different recording experience for Jarrett altogether. For some time he had to put up with Dewey Redman’s tardiness. The sax player was always late to rehearsals, but on this occasion it impacted a live performance situation. In May 1976 the band performed at Theater am Kornmarkt in Bregenz, Austria, a night recorded for ECM, later to be released as the album Eyes of the Heart. Jarrett on that night: “The long piano intro on Eyes of the Heart? That wasn’t supposed to be there. I had to keep playing because one of the other guys wasn’t on stage when he was supposed to be!”

The culprit? You guessed. Jarret continues: “Dewey Redman has a melody at a certain time, then he doesn’t, then he has a solo. Well, Dewey played the first melody then went off stage. I thought he was changing his reed or something. And then when his next entrance came, he wasn’t on stage. Meanwhile I was trying to find a way to vamp long enough so that he could find his way back to the stage. Afterwards I said to Dewey, ‘by the way, why did you go off stage?’ And he replied, ‘Oh, I just went off to get a glass of wine.’ This was not a club situation either!”

3 minutes into the track Jarrett starts vamping, stalling for 7 minutes until Redman shows up on stage, to full applause, no less. Somehow it all hangs together. This band sounded good even when killing time. Here is a section from side 2:

The group completed a European tour in May of 1976 and this was pretty much it for their live performances. Keith Jarrett focused for the rest of the year on solo piano concerts, and a short US and Canada tour to perform the Arbour Zena music live. He knew that the band was coming to an end, but he had two more albums to deliver to Impulse and he booked three recording days in October 1976. This time he took a different approach to generating material for the sessions: “I wanted to find a musically valid way, one that I would not regret later, to get the energy and finish the job – and that was to give everyone else the opportunity to write.”

The first album to be released from these sessions included music written primarily by Paul Motian, who rose up to the occasion and delivered the goods. The gifted drummer was the easiest to work with within the band, as Jarrett commented: “Paul Motian was versatile: He’s played with Arlo Guthrie , Mose Allison and with the most free players I’ve ever heard.”

In the two years preceding these sessions, Motian released two albums on the ECM label, Conception Vessel and Tribute, consisting mostly of his compositions. Jarrett was pleased with what the drummer brought to the session: “Paul, of all people, was always writing tunes. I like his stuff. He was a good drummer because he understood composition. A lot of drummers are good drummers because they have some understanding of rhythm. Paul had an innate love of song.”

Here is a fine example of his writing, the title track from Byablue:

The second album to be released from these sessions, Bop Be, comprised mostly of compositions by Dewey Redman and Charlie Haden. Keith Jarrett’s recollection this time is much different: “When I asked the other guys to write something for the album Byablue, man, did that take tooth pulling to get material. I had the feeling this was something all along that they were hoping could happen. And then when it finally became possible, they didn’t come forward.”

It is important to remember that at the time Redman and Haden were in the habit of consuming substances that hampered their reliability, making it quite difficult for a band leader to manage. Jarrett remembers: “I was like the road manager, and I was driving these guys around, and Charlie was high all the time, and Dewey was drunk all the time, and Paul was sober enough… If I hadn’t had Paul as an ally, I’d probably be in a mental institution. Ornette was backstage once, and he came up to me and he said, ‘First of all, Keith, you gotta be black. I don’t care what you say. You’re playing church music, man.’ And then he said, ‘How do you keep Charlie and Dewey in your band this long?’ Because he had them. He obviously knew everywhere we landed Charlie was gonna look for a hospital. And Dewey was gonna look for a bar.”

Still, with all these shenanigans happening in the background, Bop Be includes one of Charlie Haden’s most memorable tunes. This is the first time it was recorded, but certainly not the last, and all performances of it over the years on various Charlie Haden albums are great. Here is the original version of Silence from Bop Be:

Back in 1974 Keith Jarrett started working with a group of Scandinavian musicians in what would become known as the European Quartet. They recorded the album Belonging in 1974 and for a while were known as the Belonging band. The group included Jan Garbarek on saxes, Palle Danielsson on bass and Jon Christensen on drums. A fantastic band in its own right, and very different in style and personality from its American counterpart. Jarrett reflected on his motivation to work with that group in the face of the strong personalities in the group on the other side of the pond: “There was a reluctance in the American group to make too obvious a statement – it was like trying to pull back from obviousness, which during a certain era of jazz was the ideal of how to play. Don’t play anybody else, play only yourself. But in a way that’s impossible. There is no time when you’re only always playing yourself. In a way, that’s what the Belonging group was about. It was a relief from the American group.”

Like any good thing, the American band had to come to an end. By the time of their last studio recording, Keith Jarrett has been playing together with Charlie Haden an Paul Motian for nearly a decade, and with Dewey Redman for over 4 years. Jarrett had no illusions about such a group of people being able to stick together that long: “The American band was the democracy: four sort of radical individualists who were willing to play together. They each thought their job was to do exactly what they wanted to, and in that context I was always aware of allowing as much freedom as possible for each person to do that. It was up to me to find a way for us to continue to play together, to use the strength of individual will that was there when everyone was playing well. I knew from the start that the trade-off was going to be hard.”

At the end of 1976 Jarrett ended the band: “I remember gathering them together and saying, ‘Look, it’s been great, and we’ve done this for a long time, but this is it.’ The problems were not so much musical, but more to do with personal lifestyles.”

And so ended the journey of one of the most brilliant groups in modern jazz, a band that was the sum of its members. Listening to that band is an emotional experience, taking you from wild free-form jazz improvisations, to ethnic interludes and achingly melodic, gentle music. Truly a unique ensemble in the history of modern music.

For farther reading, visit Ethan Iverson’s excellent blog DO THE M@TH, where he featured a great interview with Keith Jarrett.

I also recommend the following books about Keith Jarrett and Impulse! Records:

Keith Jarrett: The Man And His Music, by Ian Carr

The House That Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records, by Ashley Kahn

And last but not least, visit Ted Panken’s blog, a great resource with plenty of detailed interviews with jazz musicians.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you may also like:

Categories: Artist

Thank you for this series.

Hayim, Great piece. Thanks for ending with Belonging, one of my all-time favorite albums.

Robert

Thank you for this article! I just found your site. I’m a huge Jarrett fan but have not listened to these quartet albums enough.