Previous articles in this series dedicated to recordings on various jazz labels in 1960 focused on Blue Note, Riverside and Prestige with its sub labels Bluesville, Moodsville and New Jazz. All these labels were small and closely managed by their founders, but their catalogs over the years spanned hundreds of albums each. We now come to the smallest of them all, a label that existed as a recording entity less than 12 months but in that short timeframe was able to record some of the best albums that year. Like the aforementioned labels, it was ran by a jazz enthusiast, a longtime writer and columnist about jazz artists and the genre’s history. We are talking about Nat Hentoff and his label Candid Records.

Nat Hentoff talked about how the label started: “In 1960, Archie Bleyer, then owner of Cadence Records, a pop label, asked me to start a jazz division, which was called Candid Records. Archie promised that I could record whomever I wanted, whether he understood the music or not. An honorable man, Archie kept his word, and I was never overruled.” Indeed, most of the recordings we will cover today are not easy jazz listening, and were all recorded in the short period between August and December of 1960.

On August 23, 1960 the first recording for Candid Records took place, with blues pianist Otis Spann. At the time of the recording Spann was known as Muddy Waters’ piano player, with whom he performed at the Newport Jazz Festival that year. Spann joined Muddy Waters when he was only 17, after moving to Chicago from his hometown of Mississippi. He never had any music instruction: “I played my own style. People were wondering at first, because I have short fingers. They figure I couldn’t physically play that much piano. But you can make an instrument do what you want it to do.”

Accompanying Otis Spann on this recording is the guitar player Robert Lockwood Jr., the step-son of none else than legendary blues musician Robert Johnson. Like many other blues musicians, Johnson had a large influence on Spann: “There was nobody else who had the ideas and the power or emotion he had. It wasn’t until he died that I began to develop some of my own things.”

This was Spann’s first album as a leader. He said this about his music: “Most of the people who come to hear us work hard during the day, what they want from us are stories. The blues for them is something like a book. They want to hear stories out of their own experiences, and that’s the kind we tell.”

Otis Spann − vocals, piano

Robert Lockwood Jr. − guitar, vocals

The next recording for Candid requires a little historical context, for the message it carried was as important as the music. On February 1, 1960, four young black men sat down at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. An insignificant event in current times, but a brave and daring act in 1960. The local policy, as in many other Southern states, was to refuse service to anyone but whites. The event sparked a sit-in movement that was highly covered on TV and other media. Freedom rides started a year later to protest against segregated bus terminals.

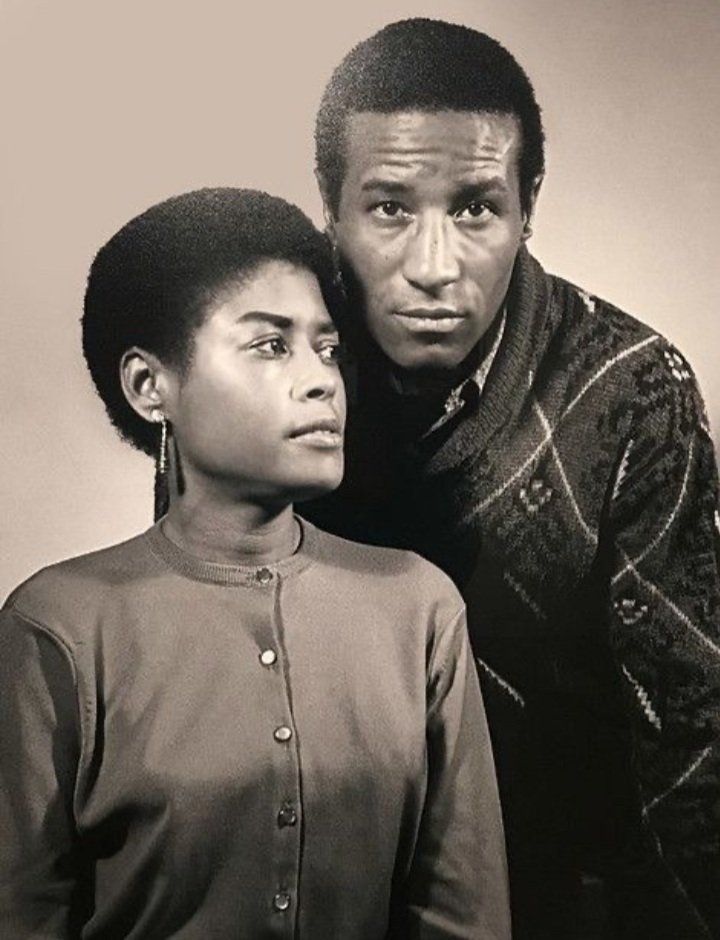

These events were sufficient drivers for drummer Max Roach and producer Nat Hentoff to bring about the album We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, recorded in August and September of 1960. Both men were highly involved and vocal about civil rights issues. Max Roach collaborated with lyricist Oscar Brown Jr. and composed five pieces that take the listener through a journey starting with slavery and continuing with emancipation, the civil rights movement and African independence.

The suite was performed as a live piece by Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln earlier in 1960. Nat Hentoff remembers attending one of these shows: “I’d seen Max and Abbey at a place called The Village Gate do the Freedom Now Suite. I said to Max, ‘Obviously, somebody has asked you to record this?’

He said, ‘No.’”

As both A&R and producer of Candid Records, Hentoff jumped on the opportunity and brought in additional musicians to the studio to record with Roach and Lincoln. Coleman Hawkins joins on the first tune Driva’ Man, a piece that deals with white slave owners and the capture of escaped black slaves. When the veteran sax player saw the music in the studio he asked, “Did you really write this, Max? My, my!” Nat Hentoff writes in the liner notes about his solo on this tune: “There was a squeak in this, his best take. ‘No, don’t splice,’ said Hawkins. ‘When it’s all perfect, especially in a piece like this, there’s something very wrong.”

Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace, a duet between Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln in three parts, sees Lincoln delivering a devastating vocal performance in the middle section. Hentoff: “Protest is a final, uncontrollable unleashing of rage and anger that have been compressed in fear for so long that the only catharsis can be the extremely painful tearing out of all the accumulated fury and hurt and blinding bitterness.” And about the singer screaming for over a minute on that track: “Abbey had the hardest job of any singer I’ve ever seen. I mean how do you make a scream into music?”

The final piece, Tears for Johannesburg, uses a 5/4 meter to propel a tune that shifts to civil rights in South Africa. Roach uses the odd meter in a much less tamed manner than Dave Brubeck on Take Five a year earlier. Hentoff writes: “Tears for Johannesburg sums up, in large sense, what the players and singers of the album are trying to communicate. There is still an incredible and bloody cruelty against African Americans, as in the Sharpeville massacres of South Africa. There is still much to be won in America. But, as the soloists indicate after Abbey’s wounding threnody, there will be no stopping the grasp for freedom everywhere.”

Max Roach – drums

Abbey Lincoln – vocals

Booker Little – trumpet

Julian Priester – trombone

Walter Benton – tenor saxophone

Coleman Hawkins – tenor saxophone

James Schenk – bass

Michael Olatunji – congas, vocals

Raymond Mantilla – percussion

Tomas du Vall – percussion

On January 15, 1961 the Freedom Now Suite was performed again at the Village Gate as a benefit concert for CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality). The concert involved musicians and dancers, one of them a young Maya Angelou.

In 1960 Don Ellis participated as a student in the Lenox School of Jazz summer program. Fellow students included future publisher of jazz education books Jamey Aebersold, Michael Gibbs, Chuck Israels (soon to join Bill Evans’ trio), Gary McFarland and future Frank Zappa Mothers of Invention member Ian Underwood. Ellis, born in 1934, was past his school days but he was immersed in Gunther Schuller’s teachings of third stream and the possibilities of combining jazz and classical music esthetics.

After the summer sessions ended, Schuller wrote about Don Ellis: “His playing represents one of the true syntheses of jazz and classical elements, without the slightest self-consciousness and without any loss of the excitement and raw spontaneity that the best of jazz always had.”

In October of 1960 Don Ellis recorded his debut album as a leader for Candid, How Time Passes. Schuller continues in the liner notes from the original album: “The impetus was his reading of a highly specialized and complex article on the function of time, also titled… How Time Passes by the young German avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen.”

The title track makes use of increases and decreases in tempo, led by the improvising soloists. This is what Downbeat wrote in its review of the album in 1961:

“Melodically and harmonically Ellis’ use of the 12-tone row is sure to prove an obstacle for many listeners. Its austerity and apparent coldness will force many listeners to shy from it on first hearing, just as its initial employment in classical music caused howls of outrage from the melodists and romanticists in the early days of Arnold Schoenberg’s and Alban Berg’s ventures. Certainly in Ellis’ thematic lines there is a harshness and utter lack of sentimentality that puts his music far outside the pale of the unsophisticated.” Fear not, I find this music very communicative.

Don Ellis – trumpet

Jaki Byard – piano, alto saxophone

Ron Carter – bass

Charlie Persip – drums

At the end of 1959 Charles Mingus started a residency at a new Village club on West 4th Street called the Showplace. He stayed there until the end of October 1960, and during that time formed a quartet that was sometimes called The Jazz Workshop. The group included drummer Dannie Richmond, a young trumpet player called Ted Curson, and a multi reed instrumentalist fresh in New York from Los Angeles. That was Eric Dolphy, who fit what Mingus was looking for like hand in glove. Dolphy said this about working with Mingus: “You never know what Mingus is going to do because every night he comes on the stand with something different. He’s so creative, and in that way it was so stimulating to work with him.”

Working for months on end in a group led by Mingus is not an easy task for any musician. Nat Hentoff described the challenge in the album’s liner notes: “Mingus has served as a kind of Lee Strasberg of jazz. He has taken many men into his group and has challenged them to find themselves musically. Some have lasted only a night, others a week, and a few stayed for long stretches. The conditions of apprenticeship in the Mingus Jazz Workshop are fiercely demanding.”

Hentoff had an opportunity to record the group just before that brilliant lineup dissolved. Wishing to avoid a location recording at a club, he asked the group to perform at Tommy Nola’s Penthouse in the Steinway building, where many other albums for Candid were cut. Mingus introduces each of the songs as if there was a live audience in the place.

The session included a version of Fables of Faubus, previously performed on Mingus Ah Um. However, Columbia Records refused to allow Mingus and company to sing the lyrics to the song and it was recorded as an instrumental. Hentoff had no such issues and welcomed the mockery of the segregationist Arkansas governor:

Name me someone who’s ridiculous, Dannie.

Governor Faubus!

Why is he so sick and ridiculous?

He won’t permit integrated schools.

Charles Mingus – bass

Ted Curson – trumpet

Eric Dolphy – alto saxophone and bass clarinet

Dannie Richmond – drums

We remain with another innovator of modern jazz. Nat Hentoff recalls the first time he met Cecil Taylor at a record shop in Boston: “I was working at a radio station that allowed me to play jazz when the time couldn’t be sold to anyone. And Cecil was a student at the New England Conservatory of Music. At the record shop, everybody – including the man behind the counter – had opinions. But no one had clearer, and more unexpected opinions about music than Cecil.”

Hentoff remembers how difficult it was for Cecil Taylor to find performance opportunities with the type of music he was playing, always challenging audiences to listen to his unique interpretation of jazz. To make ends meet he had to work day jobs – short-order cook, dishwasher, delivering orders from delicatessens, clerk at a record store. Finding himself with no gigs for stretches of six months on end, he played at home for hours every day as if an audience was in the room: “I have to make that imaginative leap. I have to believe I’m communicating with somebody.”

The recording session arranged by Hentoff took place in October 1960 and yielded the album The World of Cecil Taylor. The bass player on that session was Buell Neidlinger. He recalls: “I have played with Cecil on and off since 1956. The first thing about his music that struck me was that, despite its harmonic and rhythmic complexities, the music was clear, I could see it as well as feel it.” Indeed, like Ornette Coleman, what sets Cecil Taylor’s music apart from some of his free jazz and avant garde peers, is that his music makes sense to me. Of course it requires deep concentrated listening, but it does not hurt your ears and makes for a rewarding experience.

A favorable Downbeat review of the album from March 1961 said: “Whatever else one may think of Taylor, it would be hard to deny that his playing conveys an immense, upsetting sense of urgency – much the same as could be said of Ornette Coleman. It was this immediacy which first convinced me that what Taylor is attempting is both genuine and valid.”

The review continued with: “At his best I hear Taylor creating a spontaneous, improvised Third Stream music—i.e . a true synthesis of material from jazz and contemporary classical music.” This is the opposite extreme of attempts at third stream music, to which we will go deep in the next article in this series, with recordings by John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

Perhaps the best quote about Cecil Taylor’s music came from another giant – arranger and composer Gil Evans: “All I can say about Cecil as a composer and pianist is that when I hear him, I burst out laughing in pleasure because his work is so full of things. There’s so much going on and he us such a wizard that whatever he does bristles with all kinds of possibilities.”

The album’s opening track, “Air” had to be attempted 29 times in the studio before Taylor was satisfied with the performance. Buell Neidlinger writes in the original liner notes: “During the period I write this, we are playing in The Connection at the living Theatre in New York. It’s interesting to me that Cecil is using pieces which conform absolutely to the mood of the instant we start to play. We play three pieces in each act. Air comes at the end of the first act, at the most agitated moment of despair. Air has a pleading quality balanced against a relentless pulse. The combination was described by a friend in the audience as ‘controlled chaos.’”

Cecil Taylor – piano

Buell Neidlinger – bass

Denis Charles – drums

Archie Shepp – tenor saxophone

From Cecil Taylor we move to a member of his quartet between 1956 and 1957, soprano sax player Steve Lacy. While there have been a number of jazz greats who played the instrument, including Sidney Bechet and John Coltrane, none of them focused on the soprano sax as their sole instrument as Lacy did. He talked about the instrument: “It can fulfill an extremely valuable function in today’s jazz. Like all saxophones, its range, with practice, can be increased beyond the normal limits to four full octaves. It is the only treble instrument able to be played percussively enough and with enough power and brilliance to fit into the stylistic demands of contemporary jazz.”

In 1960, after being noticed by Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot club in New York when he played Monk’s tunes with Jimmy Giuffre, he was hired by the pianist, thus expending Monk’s group to a quintet. Lacy about that experience: “I was the happiest sideman in the world. I would play all night and practice all day. Playing with Charlie Rouse and a fantastic rhythm section taught me many things. Playing the same tunes every night gives you something to set yourself against. They are constant, but you are different each time.”

Over the years Steve Lacy became one of the primary interpreters of Monk’s music, featuring a large number of pieces from Monk’s repertoire on his recordings and live performances. He said this about Monk’s music: “Monk’s harmony comes from the melody. If you just play from the harmony, you’re missing something. Monk has got his own poetry and you’ve got to get the fragrance of it.”

In November 1960 Lacy recorded the album The Straight Horn of Steve Lacy for Candid Records. He is joined by baritone sax player Charles Davis, making for an interesting front line with the two extremes of the saxophone family. The rhythm section includes two musicians who previously played with Thelonious monk.

Steve Lacy – soprano saxophone

Charles Davis – baritone saxophone

John Ore – bass

Roy Haynes – drums

We return to the blues with an artist who was discovered by white audiences after 20 years of a career performing predominantly to blacks in the south. In 1959 blues researcher Mack McCormick contacted Lightnin’ Hopkins with the goal to expose him to a broader audience. Country blues was making a comeback at the heel of the folk revival, however Hopkins was reluctant to take the leap and perform the music to audiences who did not share his background and life experiences. Early in 1960 he started performing in Houston and California to mixed race audiences, an experience that one viewer summarized: “Lightnin’ figures that white audiences never had experienced the hard blues he knows. He’s got a leg scar, among other memories, from the chain gang. To them, he’s an exotic. And so he only gives them a small part of himself. It is very difficult for him to sing seriously of the sorrows or tragedies to a group of strange white people. He prefers to pluck for the easiest response, to make them laugh.”

Like the folks at Prestige, who jumped on the opportunity to record Hopkins twice in October and November 1960 for their Bluesville sub label (previously covered in this article series), Nat Hentoff also brought the singer to the recording studio in November 1960, this time for a solo session. It truly represents his music with a repertoire close to his heart.

Nat Hentoff remembers the recording session and particularly the conclusion of it: “When I thought it was over, Lightnin’, who had begun to pack up, suddenly took his guitar out again. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘I like the way it’s gone so far so I’d like to try some piano on the same song. I haven’t done that before on records, and I want this one to have something special.’”

What ensued was the album opener, Take it Easy. Nat Hentoff: “Lightnin’ sat at the piano, worked his guitar so that his hands were free for the keyboard but could also switch instantly to the other instrument, and he started Take it Easy. As usual, the guitar became a second voice, sometimes even more mournful and caustic than the singing. At some point, Lightnin’ briefly played both piano and guitar while singing. There was no overdubbing.”

Lightnin’ Hopkins – guitar, vocals, piano

We end the article with the solo debut as a leader by pianist Jaki Byard, who would later become a member of Charles Mingus’ band. Byard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts and mastered a number of musical instruments before focusing on the piano. He was a member of Herb Pomeroy’s band and performed at the famed Stable Club in Boston in the early 1950s. Byard told a story of his time there and meeting Charles Mingus:

“I first met Mingus in 1956 in the Athens of America — Boston. He was appearing at a joint on Commonwealth Avenue called Storyville. I was at the joint across the street. Its formal name was The Stables, but we used to call it the Jazz Workshop. Tuesdays and Thursdays, I played tenor sax with Herb Pomeroy’s big band; the other nights, I played intermission piano. Mingus and his sidemen would drop by frequently — to check us out, I guess. Since his group was called the ‘Jazz Workshop,’ of course there had to be a few words with regard to who had a better right to use that title. The matter was usually discussed by Mingus and Varty Haratunian, who was sort of the coordinator of financial affairs at The Stables. Even during an argument, their conversations were conducted very intelligently: For example, Varty might explain that our group was actually the ‘Jass Workshop,’ to which Mingus would respond ‘Yeah, take the ‘J’ off and that’s what you have for a workshop!’”

Jaki Byard plays on a couple of albums recorded in 1960 that were reviewed in the previous article in this series about the Prestige New Jazz sub label: The classic early Eric Dolphy albums Outward Bound and Far Cry. This is what Byard said of Dolphy:

“What can I say about this gentleman? His mind, as you can hear, was very active, musically intelligent, innovative, and emphatically involved with precision and decision. Eric was not only multi-faceted in his musical approach, but was also a most introspective individual. Without doubt, we were always ready to go into space together — from my very first musical association with Eric, when I played piano on his first album, Outward Bound.”

In December of 1960 Jaki Byard recorded a solo piano album for Candid, Blues for Smoke. Alan Bates writes in the liner notes: “Diane’s Melody is probably Jaki Byard’s best known composition. In the early fifties he recorded this tune with Charlie Mariano for the Imperial label and Serge Chaloff, the baritone virtuoso, also picked up this piece for his album ‘Boston Blow Up’.”

Jaki Byard – piano

Read more about jazz and blues recorded in 1960 on other labels:

Categories: A Year in Music