“It was hell, sheer hell”, summarized Roger Waters the experience of working with film director Michelangelo Antonioni. The result of that collaboration appeared on the first 1970 album to feature music by Pink Floyd – the soundtrack from the famed director’s movie Zabriskie Point. This was not the first time Pink Floyd were involved in a film project. The original lineup of the band with Syd Barrett appeared in the 1966 documentary Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, where they played a lengthy version of their cosmic psychedelic bonanza known as Interstellar Overdrive. In 1968 Peter Sykes’ black-and-white film noir The Committee included an early version of their tune Careful with That Axe, Eugene. In 1969 they were commissioned by director Barbet Schroeder to write the full score for his film More, a project they completed in eight days. Such was not the faith of their next film project.

In 1966, the year he released his milestone movie Blow Up, Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni met Pink Floyd in London at a party thrown by the underground paper IT (International Times). He kept his ears open to the music the band released in the late 1960s, and when he heard Careful with That Axe, Eugene, he decided to work with them on his next film. The four members of the group found themselves in December of 1969 ensconced in the luxurious Hotel Massimo D’Azeglio in Rome, benefitting from the large investment MGM made in the production of the film. But all was not fine when it came to working with the director. Roger Waters remembers: “We could have finished the whole thing in about five days, but Antonioni would listen and go ‘eets very beautiful, but eet’s too sad’, or ‘eet’s too stroong’. It was always something that stopped it from being perfect. You’d change whatever was wrong and he’d still be unhappy. It was hell, sheer hell.”

Drummer Nick Mason adds his view of this impossible working relationship: “Each piece had to be finished rather than roughed out, then redone, rejected and resubmitted – Roger would go over to Cinecittà to play him the tapes in the afternoon. Antonioni would never take a first effort, and frequently complained that the music was too strong and overpowered the visual image.”

Pink Floyd ended up staying a month at the hotel, producing music to meet Antonioni’s demands. The process finally ended with only three tracks being used in the film, while 50 minutes of recorded music did not make the cut. The band tried their best at the key love scene in the desert, trying various styles and moods, none of them to the satisfaction of the perfectionist director. He ended up picking a solo guitar piece performed by Jerry Garcia.

Pink Floyd made good use of the rejected tracks, which found their way into future Pink Floyd albums. A good example is the music that was originally planned for the ending explosion scene, at the time named ‘The Violent Sequence’, which later became Us and Them on the album The Dark Side of the Moon.

Many scenes from the film were shot in Death Valley, California, one of the hottest places in the world. The film had a large budget, backed by MGM who were planning to capitalize on the counterculture youth market. $7m went into the making of the film, a huge amount at the time, and five times the budget that went into Antonioni’s previous film, Blow Up. It proved to be a financial disaster, bringing in less than $1m. The film ends with an explosion scene accompanied by the track Come In Number 51, Your Time Is Up, a re-working of Careful with That Axe, Eugene. The track was first released in 1968 as a B-side single and then on the band’s 1969 double-album Ummagumma. It fits perfectly as a powerful ending to the film, accompanying the slow motion explosion:

In 1969 Pink Floyd staged a number of performances titled “The Massed Gadgets of the Auximines”, also known alternatively as “The Man and The Journey”. The two 40-minute sets included songs from the soundtrack to the movie More and a few tracks from the soon to be released album UmmaGumma. During the last show of that series, at Albert Hall in June 1969, they invited the brass section of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Norman Smith, as well as the Ealing Central Amateur Choir of women. This was a period of experimentation for rock groups and classical musicians, with bands like The Nice and Deep Purple trying to stage collaborations between the two vastly separate idioms.

Pink Floyd found the experiment satisfying enough to try their hands with a more elaborate one of the same kind. At the beginning of 1970 they had written sufficient material for a suite of music that they originally titled “The Amazing Pudding”. Dave Gilmour said of the suite’s main title: “The whole main theme came out of a little chord sequence I had written, which I called ‘Theme from an Imaginary Western’ at the time. It sounded like ‘The Magnificent Seven’ to me.” The band kept working on that theme until they had a full LP side-length worth of music. Gilmour: “We sat and played with it, jigged it around, added bits and took bits away, farted around with it in all sorts of places for ages, until we got some shape into it.”

Pink Floyd recorded the backing tracks for the suite in the spring of 1970. The next step was to compose and orchestrate additional music for a brass ensemble and a choir. Since none of them had the musical know-how of scoring music, they engaged the talents of Ron Geesin, with whom Roger Waters collaborated on the music for the documentary film The Body. In May 1970 Pink Floyd went on a tour of the US, and with minimal instruction left Geesin to come up with the music to complete the suite. Geesin recalls: “Rick Wright looked over the choir section with me for maybe half a day, and Dave Gilmour suggested a riff for one part. Roger couldn’t read music and just kind of accepted that this bloke Geesin was getting on with it. There was no great creative input from them.”

Geesin was able to take otherwise disjointed pieces of music, add melodic structures over them and combine it all into a coherent suite of 24 minutes. The task was difficult given the nature of the recordings he was handed by the band. Geesin: “There were problems with tempos because of the way they laid down the original tracks. There were variations between sections that weren’t due to any progression, just to an accident – dropping back in tempo when it really should have increased a bit; or it would be better to have a sudden change instead of a very slight change.” The tempo issues continued from the writing desk to the recording studio when the hired classical musicians had to play over Pink Floyd’s uneven recordings: “It was a problem to get the tempo right. It’s normal anyway for classical musicians to have problems with the beat. Classical beat sense and rock beat sense are quite different.”

The difficulties of working with the classical musicians were most acute when it came to the brass players. The suite opens with a series of staccato notes played by the brass section before the main melody settles in. Geesin: “What I wrote for that very strange stuttery introduction was actually meant to be far more stuttery, but to play it at the speed I’d written proved pretty well impossible for those players.” But the most challenging obstacle for Geesin, who had a background in jazz and improvised music, was the vast gap in attitude between himself and the classical musicians: “I was faced with top-end session musicians, booked by the system. These high-end musical laborers waited for instructions, and I waited for them to smile just a little bit, to give off some signal that they might be interested and involved.”

The recording session was saved by John Alldis, the conductor of the choir who was booked to record their parts at a later date. He came to visit the proceedings and, noticing Ron Geesin’s increasing frustration with the brass players, took over the conductor seat and got a decent performance from the indifferent musicians. Listening to the end result, you couldn’t tell that any of these shenanigans went on in the studio. The recording is a fantastic achievement for its time in the way that a rock band and classical instrumental and vocal music blend together. Part of the credit goes to a young Alan Parsons on his first studio work with Pink Floyd, acting as recording and mixing engineer.

In June of 1970 Pink Floyd was invited to play at the Bath Festival of Blues and Progressive Music. They played the full suite, still named ‘The Amazing Pudding’, accompanied by the John Alldis Choir and the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble. The band took the stage at 3am, not uncommon for a rock band but way past bedtime for the classical musicians. The show is also significant for marking the first appearance of David Gilmour with the 1969 Fender Stratocaster, soon to become legendary for the amazing solos Gilmour played on it on the band’s 1970s albums.

A month later the band played the piece at John Peel’s Sunday Concert BBC radio program. They finally decided to give the suite a permanent name. Gilmour remembers: “We got out an evening paper at Ron Geesin’s suggestion, and there was a story about a woman having a baby who had this thing put in her heart. Upon seeing the headline Atom Heart Mother, Roger said, ‘That’s a nice name. We’ll call it that.’”

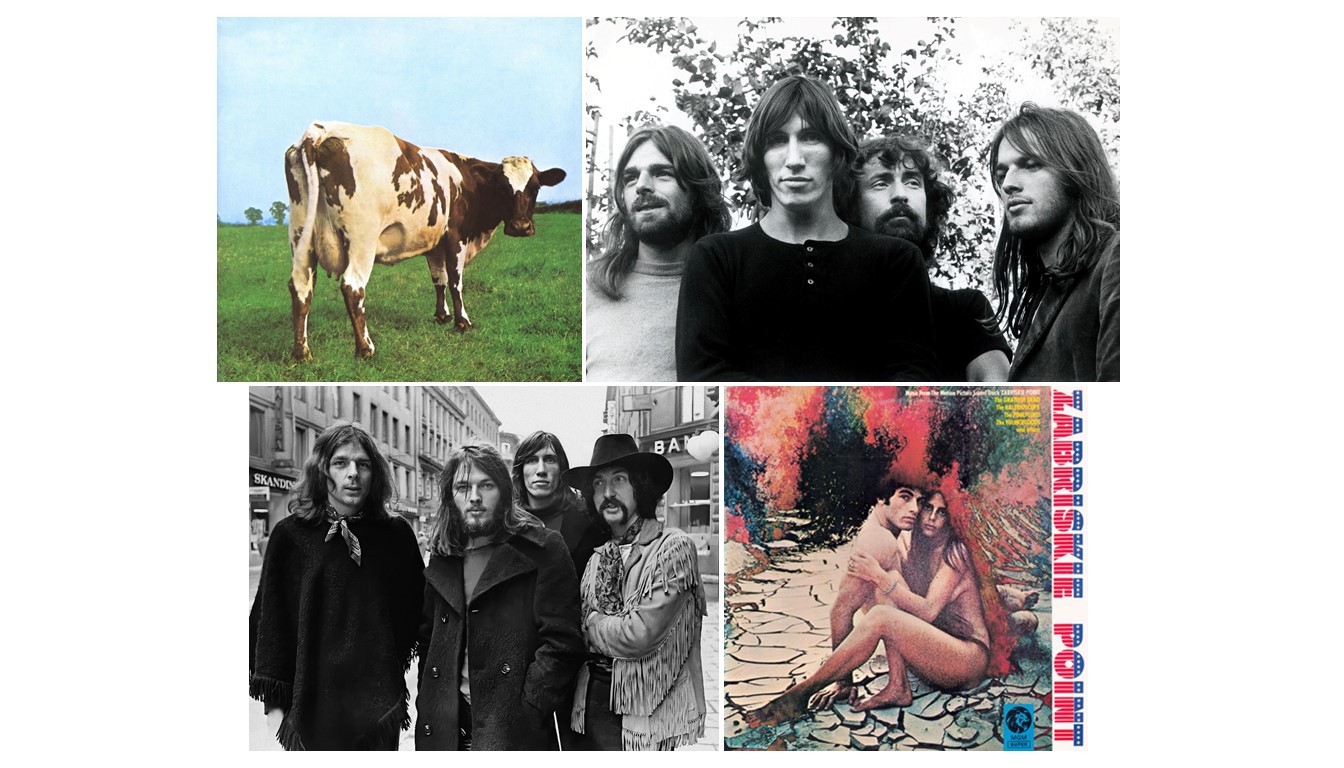

That title also gave Pink Floyd’s next album its name. Atom Heart Mother was released in October 1970 and was the first of their albums to reach the top of the album chart in the UK. It was also the first to not feature the band’s name on the front cover. Instead, album buyers in record store got the beautiful Lulubelle III gazing at them. The band asked for something plain on the cover and got a picture of the first cow Storm Thorgerson of Hipgnosis saw at a farm in Essex. He told the story: “The Floyd were deep in experimental mode. The band had no title, no definite theme, no great concept so I wanted to design a non-cover – not shocking, just unexpected. It was so different the record company almost died – the managing director had absolute apoplexy, he went all red in the face, and was reduced to swearing at me.” The cow also inspired the band to title some of the suite pieces ‘Breast Milky’ and ‘Funky Dung’.

Reviews of the album in the music press were mostly favorable, with Melody Maker leading the crowd with quite a comparison between the Atom Heart Mother suite and a work by a bona fide classical composer: “The work has plenty of shifts of texture, but maintains a mood of superb relaxation which feels very good – rather similar to the effect of Vaughan Williams’ ‘Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis’.”

Atom Heart Mother generated interest not only among rock audiences who were looking for ambitious efforts by contemporary bands of that time, but also with folks from the classical music world. They were not always impressed, mind you. Gilmour remembers an episode: “Leonard Bernstein came to one of our American concerts and he was bored stiff by Atom Heart Mother but he liked the rest.” On the other hand, the suite got the band a spot at the Festival de Musique Classique in Montreux, Switzerland in 1971. They were the first rock band to receive an invite to perform at this prestigious event.

Sources:

Zabriskie Point Original Soundtrack 1997 edition liner notes by David Fricke

Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd, by Nick Mason

Pink Floyd – Atom Heart Mother, The High Resolution Masters booklet

Leave a Reply