“Between two Aprils I lost two friends/Between two Aprils magic and loss…”.

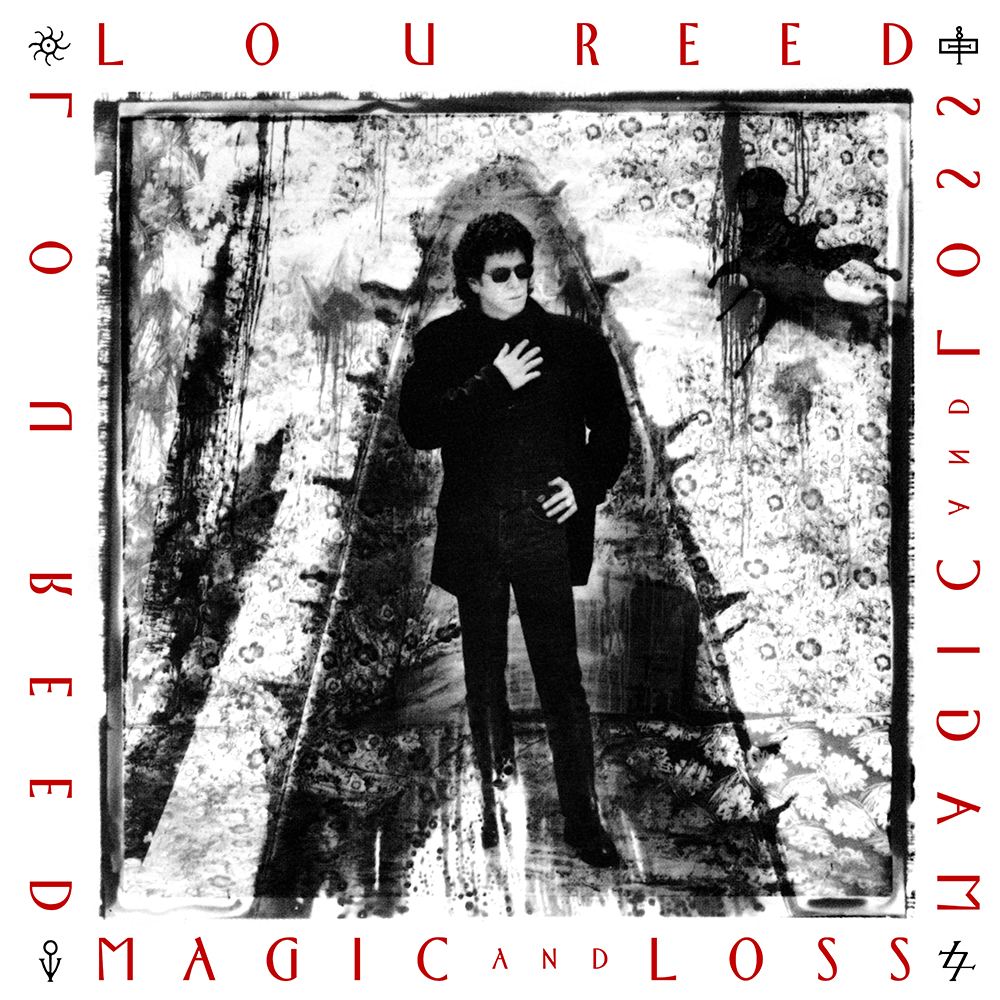

The short inscription Lou Reed wrote in the liner notes to his 1992 album Magic and Loss is the backdrop to one of the most inspired albums of his career. At the end of the album credits he wrote: “This album is dedicated to Doc and especially to Rita”. While he preferred to keep the identity of Rita away from the public (“Rita wouldn’t have wanted

Doc Pomus was one of the most prolific songwriters of the 1950s and 1960s. He contracted Polio as a child in the 1930s, but his love of music did not deter him from starting a career as a blues singer in the 1940s. You can only imagine the sight of a white Jewish singer on crutches singing in blues joints. Collaborator Mort Shuman said of him: “Doc Pomus was a white negro before it became fashionable. He sang in clubs that even some of his black friends were afraid to enter.” Pomus started to write songs for artists on the then-young Atlantic label, including Big Joe Turner and Laverne Baker. He first scored a hit in 1956 with Lonely Avenue, performed by Ray Charles.

A year later he started collaborating with pianist Mort Shuman and they quickly became one of the legendary duos at the Brill Building hit machine. Writing 12 songs a week, they generated hits by sheer volume of output. Many of these hits are classics now, including 15 hits they wrote for Elvis Presley, such as Little Sister in 1961 and Suspicion in 1962. Together they also wrote what would become Doc Pomus’ most memorable song, Save The Last Dance For Me, originally performed by the Drifters in 1960. The song is deceivingly a simple love song:

You can dance

Every dance with the guy who gives you the eye

Let him hold you tight

But don’t forget who’s takin’ you home

And in whose arms you’re gonna be

So darlin’ save the last dance for me

However given his physical disability the song carries a much deeper meaning. During the recording session, Atlantic label head Ahmet Ertegun told the Drifters’ lead vocalist Ben E. King that Pomus wrote the song after watching his wife dancing with others on their wedding night. Moments later an almost tearing King delivered a career defining vocal on this song.

In the 1980s Pomus started conducting songwriting workshops in his apartment, where artists such as Tom Waits and Mac Rebennack would come and share their knowledge and exprience. Lou Reed lived a couple of blocks away and used to stop by as well. The two struck an unlikely friendship that seemed to have a mellowing effect on Reed. They listened to old blues records together and talked about songs and songwriting. Pomus was hospitalized in January 1991 after being diagnosed with lung cancer and given three months to live. He never lost his sense of humor, and when Lou Reed offered to replace the small black and white TV set in his room with a large color set, Doc answered: ‘Lou, this isn’t the time for long-term investments’. On January of 1992, the month Magic and Loss was released, Lou Reed talked about Doc Pomus during an interview to the LA Times: “I just knew him a couple of years, but I used to love to pop over to his apartment. He was one of those people who are like the sun. You just feel great when you are around them. He doesn’t have to say anything. You just walk in and . . . boom! . . . you feel great. I think his music contained a bit of that. This was a guy singing in blues clubs on his crutches. When I was in the hospital with him, he said he was working on a song and he showed me the lyric: ‘Life’s Killing Me.’ You don’t run across people like that.”

One of the blues and jazz singers Pomus and Reed were listening to was Jimmy Scott, another legendary and forgotten figure at the time. Like Pomus, Scott overcame physical limitations and in the 1950s sang with his beautiful high voice in front of the Lionel Hampton orchestra on songs such as Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool. Doc Pomus knew Jimmy Scott since 1945 and they shared similar popular decline by the mid 1960s. In an ironic chain of events, Pomu’s funeral served as Scott’s career relaunching pad. Scott sang at the funeral and was discovered anew by founder of Sire records who signed him to a record deal. David Lynch gave him a cameo role in the closing episode of Twin Peaks in 1991, an unforgettable scene in the Red Room with the Man from Another Place dancing and Jimmy Scott singing Sycamore Trees. Lou Reed was also in attendance at Doc Pomus’ funeral and heard Jimmy Scott singing Someone To Watch Over Me, as requested by Pomus before he died. Sylvia Reed remembers: “That moment when Jimmy Scott got up and sang at Doc’s funeral was one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever had. Lou loved that sound and particular type of voice, and never forgot it.” The result was the song Power and Glory on Magic and Loss on which Scott sings a single line “I wanted all of it” which he very effectively repeats after each verse.

The song’s lyrics tackle the topic of transformation, both magical and real:

I saw a man turn into a bird

I saw a bird turn into a tiger

I saw a man hang from a cliff by the tips of his toes

In the jungles of the Amazon

I saw a great man turn into a little child

The cancer reduced him to dust

His voice growing weak as he fought for his life

With a bravery few men know

Lou Reed took a minimalist approach when planning the musical texture of Magic and Loss. Sonically this was a continuation of his two previous albums New York and Songs for Drella. In 1989 after the release of New York he told Rolling Stone magazine: “When we were recording New York there were instances in the studio when I’d come with yet the fiftieth guitar part and we’d then have to spend time taking things out. I would put down this guitar lick and go, ‘Ah hah, listen to the tone of this, how do you like that part?’ And Fred [Maher] or Mike [Rathke] would say to me, ‘It’s a great part but unfortunately it just knocked the bass out and it’s stepping all over the other guitar part and you can’t hear either one now.’ ‘But don’t you love it?’ I’d say [laughing] and they’d say, ‘We love it but. . .’ So the nice thing about our going minimal was that you could then hear the guitars and all the parts and the words and the full breath of the voice. But the dangerous thing about going minimal is that you’d better be good because your voice isn’t going to be layered under tons of things.” Songs for Drella, released a year later, went farther by eliminating the rhythmic component of bass and drums and leaving only Reed and John Cale on vocals and their respective instruments. With Magic and Loss Reed went back to a quartet format, but the minimalistic trend continued: “This is, I think, an advance over Songs for Drella and over New York, along the lines of taking things out. I’m always trying to get the gist of it without an extra word. That’s the way the guys played, too. It was all about taking stuff out. Less really is more. I truly believe that. You hear better. So you hear more. And it better be played well. One false step and it falls on its face.” Indeed you can hear superb playing on this album by all musicians involved.

Guitarist Mike Rathke started working with Lou Reed in 1987 when he was 24, and shortly after was a vital part of Reed’s first great record of the 1980’s, New York. Bassist Rob Wasserman remembers: “Mike was a very big part of it, almost like the music director. I really locked into his rhythm guitar playing, and it was basically like a trio in the beginning.” That was the start of a 22 year musical relationship between Rathke and Reed. Not only musical, as for a period of time during the 1990s Rathke was Reed’s brother-in-law having married Sylvia Reed’s sister. On Magic and Loss he co-wrote five of the songs with Reed and shared the producer credits with him. His guitar leads and use of a Casio guitar synth play a huge part of Magic and Loss’s somber mood. The Casio guitar is featured heavily on Sword of Damocles, a song about the unsuccessful chemotherapy treatment Doc Pomus had to go through:

I see the sword of Damocles is right above your head

They’re trying a new treatment to get you out of bed

But radiation kills both bad and good

It can not differentiate

So to cure you they must kill you

The sword of Damocles hangs above your head

Bassist Rob Wasserman first collaborated with Lou Reed when he invited him to sing on his Duos album in 1988. They give a unique performance of One For My Baby (and one more for the road) on that album. That led to Wasserman joining Reed for the New York album and subsequent tours. A year prior to working with Reed on Magic and Loss, Wasserman played on a couple of tracks on Elvis Costello’s Mighty Like a Rose, including the atmospheric Broken. On Magic and Loss Wasserman plays a Clevinger 6-string electric upright bass, a hybrid between a fretless and upright bass. A great example of how it sounds in Wasserman’s able hands is the album closer Magic and Loss – The Summation, which ends with the acceptance of the cycle of life and death:

There’s a bit of magic in everything

And then some loss to even things out

Unlike the two other musicians accompanying Lou Reed on Magic and Loss, Michael Blair was a new addition, and a wonderful one at that. Blair is a master percussionist who plays a wide variety of drums and percussion instruments, and he added tasteful colors to some of the best songs recorded in the 1980s and 1990s. You can hear the impact of his multi percussion contributions on songs such as Tom Waits’ Clap Hands from Rain Dogs, and the famous marimba part on Elvis Costello’s cover of Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood. One of his most effective accompaniments is on one of my favorite Elvis Costello songs, God’s Comic from the Spike album. Blair’s credits list on Spike sounds like the contents of a thriving pawn shop: glockenspiel, marimba, tambourine, xylophone, bells, timpani, vibraphone, Chinese drums, Oldsmobile hubcap, parade drum, anvil, whiplash, crash-box, temple bells, snare drum, magic table(?), metal pipe, Martian dog bark(??). His role with Lou Reed did not require him to stray off the drum set much, but he plays interesting drum parts even on a standard mid-tempo rock song such as What’s Good.

Reed contributed the song to Wim Wender’s movie Until the End of the World before the release of Magic and Loss. In the song Reed sings “You loved a life others throw away nightly”, a reflection on the irony of the value of life: “It struck me that here was this person fighting desperately for life, while just two blocks away people are shooting it away or drinking it away or doing terrible, reckless things. They don’t give a damn about their lives.”

Luckily a few videos exist showing the band that recorded the album performing live versions of the album songs. What’s Good was played at the Arsenio Hall show in May of 1992 and the full album was performed during the Magic and Loss tour in 1992.

Three songs on the album sound like posthumous meditations that Lou Reed wrote as if he is conversing with his now dead friends during three stages of their death. The sparse arrangements on these songs are an exercise of musical restraint that balance the deep emotional content portrayed in them.

Dreamin’ reminisces on Reed’s visits to the hospital:

You sat in your chair with a tube in your arm; you were so skinny

You were still making jokes; I don’t know what drugs they had you on

You said: “I guess this is not the time for long term investments.”

You were always laughing, but you never laughed at me

Goodby Mass describes the feelings during the funeral service:

Sitting with my back straight, it becomes hard to hear

Some people are crying; it becomes hard to hear

I don’t think you’d have liked it; you would have made a joke

You would have made it easier; you’d say “tomorrow, I’m smoke.”

Cremation reflects on the inevitable end that awaits us all:

There are ashes split through collective guilt

People rest at sea forever

Since they burnt you up

Collect you in a cup

For you the coal black sea has no terror

Now the coal black sea waits for me, me, me

The coal black sea waits forever

When I leave this joint

At some further point

The same coal black sea will it be waiting

The odd one out on the album is Harry’s Circumcision, which Rolling Stone magazine described in the album’s review in January of 1992: “It is based on the real-life tragedy of Lincoln Swados, the brother of writer-composer Elizabeth Swados and Reed’s roommate at Syracuse University in the early Sixties, who suffered from schizophrenia and died, homeless, on the streets of New York in 1989.” Reed said of the song in an interview after the album’s release: “there’s a song called ‘Harry’s Circumcision’, which you can take in a couple of ways. And one of the ways is that it’s funny. I think I get classified in the black humor section… which I don’t really think is true, myself.”

Magic and Loss was released on January 14, 1992. Despite its difficult subject matter it became one of Lou Reed’s most successful albums. The single What’s Good topped the Modern Rock Tracks Billboard chart and the album reached a new high for Reed, No. 6 on the UK LP chart. Asked if he was surprised by the unlikely popularity of the album, Reed responded: “Astonished would cover it. It’s very strange. In a sense it’s my dream album, because everything finally came together to where the album is finally fully realized. I got it to do what I wanted it to do, but commercial thoughts never entered into it, so I’m just stunned.” Reviews were mostly favorable spare an idiotic one by Robert Christgau calling it the dullest Reed album since Mistrial and not worth of repeated listening. Oh well.

My favorite song on the album is Magician, one of the most chilling songs I know. In it Reed not only experiences the slow and painful death of a friend, he becomes one with the friend and tells the experience from a dying persons’ harrowing view:

I want to count to five

turn around and find myself gone

Fly me through the storm

and wake up in the calm

In the interview to LA times in 1992 Reed talked about the origin of Magic and Loss: “I was originally going to write an album about magic . . . the desire for magic in life . . . the magic of transformation . . . the idea of a man turning into a bird. I had some friends who told me about some things and I was thinking about all that.” Transformation is a thread that links many of the songs on the album and on Magician it takes the form of transcendental power that can lift the soul away from a decaying body:

I want some magic to sweep me away

Visit on this starlit night

replace the stars the moon the light – the sun’s gone

Fly me through this storm

and wake up in the calm …

I recommend listening to the whole album from start to finish. It is a painful listening experience, and while some listeners may find it too depressing, I see in it a healing quality. Reed expressed similar sentiments after the release of the album: “I just hope it doesn’t start getting thought of as this terrible down death album, because that’s not at all what I mean by it. I think of it as a really positive album, because the loss is transformed magically into something else.”

If you enjoyed reading this article, you may also like this about a personal tragedy that led to a triumphant album:

Leave a Reply