After dedicating three articles to various singer-songwriters in 1970, plus two articles about Elton John and Cat Stevens, we conclude the mini-series with a collection of lesser-known artists who did not achieve the same success as those discussed earlier, but still released wonderful albums in 1970.

We start with two artists associated with Elektra Records, the label that released Tim Buckley’s albums, covered in article #2 in this 1970 singer-songwriter series. David Ackles’ dream was to write musicals, ballet scores and choral pieces. He joined Jac Holzman’s Elektra Records as a songwriter with no initial ambition to perform. At the suggestion of the label head he released a self-titled debut album in 1968. Holzman remembers the artist and his creative forces: “David Ackles was fascinating, because he was really a composer of musicals for a very small stage. His albums were like intimate musicals. You could have taken the songs and later written a book around them. He was beset by so many demons, which appear in disguise within his songs – but that’s why he has to sing them. Ackles was very kind and considerate, an extremely gentle soul who lived within himself and within his music.”

[Subway to the Country]

In 1970 Ackles released his second album, Subway to the Country. The song topics cover a wide variety of dark themes, from shady and smelly saloons to child molesters, women-beaters, and if that wasn’t enough he threw in a scene of the gallows. Musically you can hear the influences of cabaret music by Kurt Weill in equal measure to country and folk music. Sound engineer Bruce Botnick, who worked on many classic Elektra albums by the likes of The Doors, Love and MC5, talked about the songs of David Ackles: “The music may have been intense, but he was a marshmallow: one of the sweetest people. He was obviously conflicted and a complicated person. You don’t write about the subjects he engaged with unless it’s to deal with demons. He was uniquely Elektra in temperament, with a Jacques Brel quality, dark but also charming. Ackles had the perfect voice for what he was doing, although he was by no means a perfect singer.”

The album is host to many of Los Angeles’ best session men, including Victor Feldman, Jim Gordon, Larry Knechtel, Jim Horn and others. One of the most profound musical contributions is by a friend of David Ackles, arranger and conductor Fredric Myrow. David Ackles’ wife Janice Vogel Ackles remembers the gifted arranger: “Fred Myrow was certainly from a very classical background and discipline. He added some really interesting things, tonally, to the album. I know that David was extremely pleased about that.” His excellent orchestral arrangements compliment David Ackles’ theatrical music beautifully. A fine example is That’s No Reason to Cry, a song that reminds me of Scott Walker:

David Ackles had many fellow musician fans, among them Elton John and Bernie Taupin. They met at the Troubadour club in Los Angeles when Elton John performed there in 1970. Bernie Taupin went on to produce Ackles’ next album, his masterpiece American Gothic. He said it well: “In the golden age of the singer-songwriter, David was a hybrid disconnected from the troubadour label pinned on others. It’s not just that his music was different, he was different.”

We move to the next artist in this review, who in addition to performing his own songs is well known for recording songs written by other songwriters. Before they were famous, Tom Rush recorded songs by Joni Mitchell (“Urge For Going,” “The Circle Game”), James Taylor (“Something in the Way She Moves,” “Sunshine, Sunshine”) and Jackson Browne (“Shadow Dream Song”).

In the late 1960s Tom Rush recorded a number of albums for Elektra Records, among them ‘The Circle Game’. In an interview he said, “The album reputedly started the whole singer-songwriter movement. But I wasn’t trying to start any movement, or discover any artists, I just needed some good songs. I was overdue for delivering an album to Elektra. And these were fabulous songs that I thought I could do – I could add my own perspective to them.”

In 1970 Tom Rush changed record labels and signed with Columbia Records. He released his first album with that label in March of that year, the self-titled Tom Rush. Continuing his custom of including songs written by upcoming songwriters, this time Tom Rush decided to perform a full album of such songs. About his love of picking material by talented songwriters he said, “When I’m doing other people’s songs, that’s really all I want. I want a song that gives me goosebumps, that I think I can do something different with. I don’t want to just mimic the original. In fact, when I’m learning a song I stop listening to the original, then as I’m playing it, it gradually comes loose from its moorings and becomes different.”

Among the songwriters who contributed their songs to the album are Murray McLauchlan, James Taylor, Jesse Colin Young (from The Youngbloods), and Fred Neil, known from his song ‘Everybody’s Talkin’ – a hit for Harry Nilsson after it was used in the film Midnight Cowboy in 1969.

My favorite song on the album was written by Jackson Browne very early in his songwriting career. He recorded a demo version of ‘These Days’ in 1967 for Elektra’s Nina Music publishing department. The song was first performed by Nico on her album Chelsea Girl the same year. Tom Rush became aware of Jackson Browne through Elektra Records: “Jackson Browne was not a singer-songwriter, he was just a songwriter at that point. Elektra was pumping me up with his demos. I didn’t actually meet Jackson Browne until quite a bit later.” Here is Tom Rush’s version of that great song:

We mentioned Nico, so let’s look at an album she released titled Desertshore. In 1970 Nico settled in Paris, living with film director Philippe Garrel. She acted in a number of his films, one of them La cicatrice intérieure (The Inner Scar). The front cover of Desertshore is an image from that movie, about which Nico said in 1970: “This new movie is very important to me. It’s so powerful. We did part of it in the American desert and part of it in the Egyptian desert.”

Like Tom Rush, Nico also moved away from Elektra Records, the label that released her 1968 album The Marble Index. Desertshore was released on Reprise Records and was produced by John Cale and Joe Boyd, who recalls in his memoir White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s: “I had been stunned by John Cale’s arrangements on Nico’s The Marble Index and shocked that Elektra failed to pick up its option for a second LP. I convinced Warner Brothers to finance a sequel and after a week of recording in New York, Cale flew to London to help me finish off Desertshore.”

Nico’s music is all about mood and atmosphere. A 1971 Rolling Stone review of her performance at the Roundhouse describes it well: “The combination of her voice, syllables stretched to madness and dropped, and the cavernous repetition of the harmonium slow the Roundhouse crowd down. The stage goes all black except for soft purple and green spots high above her head. The light show flickers down to a single picture, all grainy and glowing. The people stop talking. A great hall becomes a mediaeval cathedral.”

Richard Williams wrote in Melody Maker: “Nico frightens me, yet somehow draws me closer to drink from her fountain of desolation and alien fantasy; I don’t think she’s at all aware of the effect she has.” The songs on Desertshore were all written by Nico, who sings and plays the harmonium on the album. John Cale plays all other instruments except trumpet. Here is the song ‘Afraid’, a favorite from that album:

Next is a unique singer-songwriter and a great instrumentalist who released two fantastic albums in 1970. Texas-born Shawn Phillips started his recording career in the mid-1960s in London, releasing two albums on Columbia Records. He guested on a number of albums by Donovan, including Fairytale, Sunshine Superman and Mellow Yellow. In 1968, while he was living in Italy in a one-room apartment overlooking the Mediterranean, he started working on an ambitious project: “I wanted to do something different, to create a trilogy of albums that ranged through a full spectrum of music. From pop-type tunes to rigidly disciplined classical work and even narrated poetry with a musical backing track. I did this, and the entire trilogy was entitled A Contribution.”

When he presented the trilogy to A&M Records, Phillips met resistance in realizing his idea of releasing each part of the original concept as a separate album. Instead, “they made me take the trilogy apart and put eight of the songs onto one album, which became Contribution. The rest, with the exception of one or two, went on Second Contribution.”

Contribution, the first album to include songs from the trilogy, feature guest appearances by all members of the band Traffic at the time – Steve Winwood, Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood. Phillips said of the recording process: “Every single song was recorded in less than three takes, and the master vocals were not overdubbed later but were done in the same moment. Some vocal harmonies and guitar parts were later added as sweetening.”

The album’s centerpiece is Withered Roses, an interesting composition that features Phillips on a sitar, an instrument he adopted early in his career: “I started playing the sitar in Canada about 1963 or 64. I gave George Harrison his first lessons, before he met Ravi Shankar. Donovan and I got invited to George’s house and we had dinner and I sat him down and said ‘Look, here’s the basics, this is the way you sit with it, blah blah’.” The song features great singing and scatting: “Voice is an instrument and that’s what I was doing. You can hear that from some of the high notes and the falsetto that I was using.” Given the complex nature of the track, it was amazingly completed in a single take.

The songs on both albums Shawn Phillips released in 1970 are quite diverse in music styles and mood, He said this of his music: “I want everyone who hears my music to experience the sadness, perplexity, the great thoughts, the grave thoughts, the joy, the freedom, the fullness of the experiences I’ve had, which in turn, were expressed to create the music.” Bill Graham called Phillips, “the best kept secret in the music business”, and the singer added: “If you use a word like xenophobia in a song, or any word that the general public has to look up, they tend to shy away from any semblance of intelligence in popular music.”

The second of the two albums he released in 1970 was titled Second Contribution, another great record which Shawn Phillips planned as a continuous listening experience: “The thing about this record was that I wanted people to be able to put the record on and float away, on their own images that the music induced. Not for three or four minutes as was the average time for a song, but for 20 minutes, like they were listening to a symphonic work. The music starts and doesn’t stop till it gets to the end of the record.” Arranger Paul Buckmaster wrote wonderful orchestral arrangements that add to the symphonic feel of the album.

My favorite song is The Ballad of Casey Deiss, the only track that stands alone separate from the rest of the songs on the album, which are all stringed together. The song was written about a friend of Phillips: “During the initial writing period of the material on the two albums, Casey was still alive. He was struck by lightning shortly before the recording of Second Contribution, and I wrote his song just before we went into the studio.”

We end the review with two wonderful 1970 albums that, like the artists who created them, were forgotten after their release,. Luckily they found new appreciative audiences when they were resurrected many years later. The first is Bill Fay, who was signed to Deram, the progressive subsidiary or Decca Records. As he later said of the label, “Mid-sixties to seventies there were all sorts of left-of-center alternative things, like my own, that they were giving a chance to. Deram would give a chance to all sorts of people. Somebody said that they would throw several pieces of mud against the wall and hope that some would stick.” Unfortunately, after recording two albums for the label, “I was someone who just dropped off the wall.” A shame, as both albums, although very different from each other, are lost (and found) gems of that period.

Bill Fay’s self-titled debut was produced by Deram house producer and A&R man Peter Eden, who started his career working with Donovan. He was an important figure in the emergence of modern jazz in Britain around that time. At Deram he has been working with jazz artists such as John Surman and Mike Westbrook. The album’s wonderful orchestral arrangements were written by another recording jazz artist on the label, Michael Gibbs, who would go on to work with diverse artists such as Joni Mitchell, Peter Gabriel, John McLaughlin and Uriah Heep. Bill Fay recalls that, “I didn’t have any say in the kinds of arrangements. But what mike did arrangement-wise was very compatible with the songs.”

In the liner notes to the 2005 CD release of the album, Bill Fay wrote in detail about his experience being present when the orchestra recorded the arrangements for his songs: “I recall arriving slightly late on the morning of the session, and upon opening the studio door I turned to go, thinking I’d entered the wrong studio, until I spotted Mike Gibbs standing in the midst of a 27-piece orchestra. It was his first arrangement session and he confessed that he’d added various things to my songs and had been awake all night worrying, unsure if the arrangements were going to work.” Well, work they did, and amazingly the whole album was recorded in a single day.

The album got nowhere with the music press and in record shops, spare one favorable review in Zigzag Magazine. The article found similarities in the use of orchestral arrangements on David Ackles’ album. The writer added, “When I first heard the record, it was the tunes that went straight into my head and Bill’s rather fat North London voice, which was such a change from all the sub-Dylan English singers. But now it’s his lyrics I really listen to, because he does manage to say a great deal in very few words.”

A fine example of Fay’s music and lyrics can be found on the album opener, Garden Song. Bill fay wrote about the inspiration for this song: “Garden Song was the beginning of seeking something deeper. I came to feel that we were largely in our day-to-day lives asleep to a greater reality. I believed there was something to find out, but more than that, I felt strongly that you could actually find out, which was a big step for me.” The song starts with these lines:

I’m planting myself in the garden

Between the potatoes and parsley

Many of Bill Fay’s songs have a backdrop from the natural world, a choice which he explained: “I started to pay more attention to nature. I didn’t run to the mountains or anything, I mean that I would sit on the top deck of a double-decker bus and look at things, trees, for example. Part of your head is saying ‘why are you doing this, it’s only a tree’, but I kept looking, to try and understand more and get outside of my own head.”

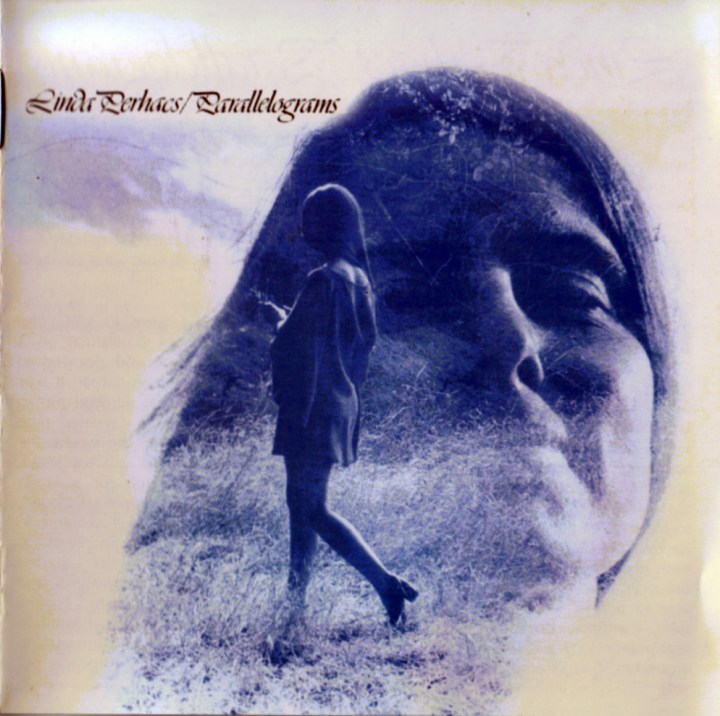

We end the article with another artist who after a sole album in 1970 left the music industry for a long period of time. That year Linda Perhacs released the album Parallelograms, one of my favorite albums from that year, an obscure gem that vanished from record stores quickly and luckily was re-released in CD format in 2008.

After graduating from the University of Southern California, Linda Perhacs settled in Topanga Canyon in the late 1960s, where “It was a rich environment, full of artistic people, and the creative level was unbelievable.” Working as a dental hygienist in the canyon, one of her clients was Oscar-winning film composer Leonard Rosenman, who scored the movies Barry Lyndon and Bound for Glory. Upon listening to some of her basic demos, he offered to produce an album with songs she kept in the drawer.

The album is a combination of Rosenman’s love of atonal classical music and Perhacs’ softer, more ethereal music using the guitar in unique ways: “For each of the songs I used individually-created tunings, using steel strings to capture the high ring in the tone and delicate arpeggios. I love to weave modal sounds and airy harmonics with electronic splashes. Standard Western chord changes are very predictable. I prefer to mix them with modal sounds to add texture and mystique.”

My favorite song on the album is the title track Parallelograms about which Linda Perhacs said: “It was the song ‘Parallelograms’ that made Leonard want to record a whole album with me. It came to me one night on the Ventura Highway, at 3am. I was driving on the empty highway, half-asleep, and the song came to me – bam! – like that. I explained to him how I envisioned the song by drawing it in picture form, on a scroll, saying it needed to be a moving sound-sculpture. He stared at me in silence, and slowly, very firmly, said: ‘Linda, do you know I could live a lifetime and only come up with maybe two concepts that unique? And I am a trained composer! This one is true composition. The others are songs.'”

Sources:

The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond, by Chris Blackwell

Categories: A Year in Music