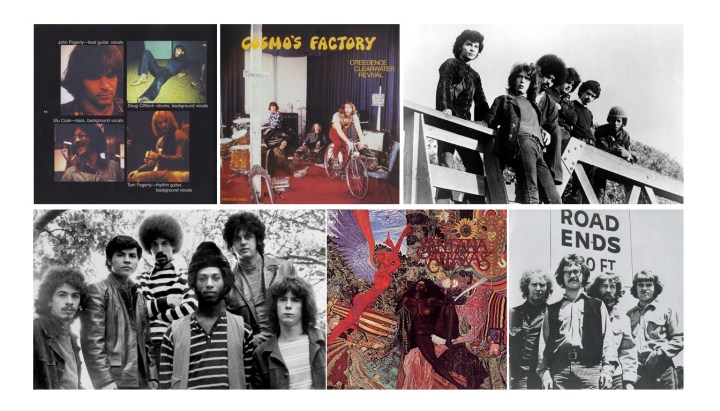

The previous article about West Coast bands in 1970 focused on Los Angeles. We now take a trip up the California coast to San Francisco and two of my favorite 1970 albums. We come to the Bay Area and meet two very successful bands who after their performances at the Woodstock festival were at their peak in 1970.

The first band recorded their self-titled debut in 1968 and then had an extremely productive run of albums over the next two years, releasing no less than five more records. Creedence Clearwater Revival was already one of the biggest rock bands in the world in 1970, with hits including Suzie Q, I Put a Spell on You, Proud Mary, Born on the Bayou, Bad Moon Rising and Fortunate Son. But then they outdid themselves and released their most successful album, the multi-million seller Cosmo’s Factory.

As band leader John Fogerty said, the album produced “Six hit singles, and this was not a greatest hits album.” The songs released as singles included Travelin’ Band, Who’ll Stop the Rain, Up Around the Bend, Lookin’ Out My Back Door, Long As I Can See the Light, and one of my favorites on the album, Run Through the Jungle. Many think that the song is about Vietnam, a natural reaction given the song title and its lyrics, which include these lines:

Two hundred million guns are loaded

Satan cries, “Take aim”

But Fogerty, who wrote most of the songs on the album, proves us wrong: “The song is really about gun control. It was really my remark about American society, the metaphor being society as a jungle. When I sang ‘Two hundred million guns are loaded,’ I was talking about the ease with which guns are purchased in America. And it is a jungle.” The song became a favorite of the American troops in Vietnam, a war that trickled into the song, as Fogerty pointed out: “At the same time, it was all mixed up in the fearmongering of Richard Nixon that had taken hold in our land.”

Run Through the Jungle opens and closes with sound effects resembling a helicopter, achieved with rudimentary equipment: “With the ‘storm clouds’ that open and close the song, I was trying to go beyond the usual start-stop. I think there’s some backwards guitar and piano on that, plus a couple of tambourines. That’s the Rickenbacker into the Kustom. One of the guitar tracks was a pick slide with slapback echo. The overall effect was ominous, spooky. I was getting a lot with just a little. It wasn’t Hugo Winterhalter or Hans Zimmer. I was just a kid in a rock and roll band trying to add some color.” Fogerty indeed uses his 1969 Rickenbacker 325 Sunburst to maximum effect on this track.

The title of the album is a reference to the setting of the cover photo. Bass player Stu Cook: “The original ‘Factory’ was a shack in Doug’s backyard. We would rehearse there Monday through Friday every week. It was a joke—we were going to our jobs like other factory workers.” Drummer Doug Clifford is pictured riding a bike at the front of the photograph. His nickname was Cosmo, and he said of the title: “It was named after me because I was the prankster, the jokester, the guy who was always saying something.“ John Fogerty adds: “Stu’s nickname for Doug was Cosmo—it had something to do with the Cosmo Topper character on the old TV series Topper. That cover made him famous. I told the guys I thought it would be cool if we took a shot of us with our favorite things near us at the Factory. I thought it was a way of fleshing out the personalities in the band. It was sort of antishowbiz.”

You will notice a sign on the post reading 3RD GENERATION. Like everything else on the front cover photo, it was carefully planned. John Fogerty explains: “The liner notes of the 1968 debut album were written by Ralph J. Gleason—that’s where he says, ‘Creedence Clearwater Revival is an excellent example of the Third Generation of San Francisco bands.’ Meaning we weren’t quite as good as the Grateful Dead or Quicksilver Messenger Service. That sign was for Ralph.”

My favorite song on the album is a cover of ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine’, made famous by Marvin Gaye’s version from 1968. The song was written by the songwriting duo Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong for Motown Records in 1966. It was recorded by Gladys Knight & the Pips before reaching Marvin Gaye who made it a soul classic.

Fogerty told the story of how he got inspired to perform the band’s version of the song: “One day I was down in Los Angeles, maybe Sunset Boulevard, in a hippie clothing shop where they had a lot of leather, vests, and hats. They had an FM radio on and the speakers were really far apart—one was in the front of the store, another way in the back. I liked Marvin, especially his early stuff, but I really hadn’t paid attention to his recent, very produced recordings, and ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine’ came on. Motown always had all that production and echo covering everything up. Because I was back there near one speaker, I was mostly hearing his voice—clear as a bell, with all his cool gospel inflections. Suddenly I was smiling—I was hearing Marvin really sing. I heard a guy really cutting it, singing his rear end off, and I was knocked out.”

Forgerty turned the tune from a piano to a guitar song, using the vibrato guitar to create the drone-like feeling of the riff. The song features a long jam and one of Fogerty’s signature guitar solos. He said of the song: “I took it into the swamp. Duane Eddy could’ve done that song. Beat you to it, Duane!” Like the rest of the album, the song was recorded with all band members playing live in the studio, with very minimal overdubs applied later. Drummer Doug Clifford remembers the recording session: “It was a free jam where we got to play off of each other. What I would do is play off of John’s rhythm. I don’t play a lot with the bass guitar pattern. John and I would trade off little rhythms. If you listen to the record, the guitar does one thing, then I’ll do something that’s kind of like it.” He also recalled that the jam was recorded to fill up space. It indeed filled 11 minutes of space on side two of the album, the kind of space I like.

Album credits:

John Fogerty – lead guitar, lead vocals, piano, electric piano, keyboards, saxophone, harmonica, producer, arranger

Tom Fogerty – rhythm guitar, backing vocals

Stu Cook – bass guitar, backing vocals

Doug Clifford – drums, cowbell

Cosmo’s Factory was recorded as Wally Heider’s studio in San Francisco, the same studio where the next album in our review was recorded. In 1970 Santana released their second studio album, the mega-selling Abraxas, yielding four singles – Black Magic Woman, Oye Como Va, Hope You’re Feeling Better and Samba Pa Ti.

Riding high on the success of their self-titled debut album and their legendary performance at Woodstock, in the summer of 1970 Santana was ready to record their second album. Expectations were high, and compared to the debut album that was based on material the band performed for a number of years, this time they had to come up with new material quickly. Earlier that year they introduced a new instrumental to their live performances called ‘Incident At Neshabur’. It was the first track they recorded for Abraxas. Carlos Santana explained the topic of the song: “Neshabur is where the army of Toussaint Louverture – who was a black revolutionary – defeated Napoleon in Haiti. So that’s what it’s about. I think by writing songs like ‘Incident at Neshabur’ and ‘Toussaint L’Overture,’ we felt we were our own kind of revolutionary.”

The song was written by Santana and Alberto Gianquinto, a piano player who worked with the band in the studio and occasionally performed with them on stage. An older and more experienced musician than the band members, he was versatile with blues, jazz and classical music and acted behind the scenes as a music adviser. He started working with the band on Incident At Neshabur during the recording of the debut album. Santana remembers: “Alberto came up with a vamp for the second part, which was basically Horace Silver’s ‘Señor Blues.’ He played piano on that, going between two chords, which set me up for a solo that sounded to me like the divinity that comes after sex, when you’re just lying there after giving it all you got and you both arrive at the same time and she’s happy and you’re happy.” Coital experiences aside, this is truly a great showcase or all band members and Carlos Santana in particular. The track was too long to fit into the debut album and had to wait for inclusion on Abraxas.

Gregg Rolie also has fond memories from the recording of that track, especially the experimentation with song structures: “Incident at Neshabur was one of my favorite things. We did time changes, chords, and things that musically were very sophisticated. It was a perfect combination of Horace Silver and Big Black, with Aretha Franklin singing that Burt Bacharach song ‘This Guy’s In Love With You’. We’d just combine things we had passion for. We didn’t consciously know what we were doing.”

The album’s name came from the book Demian by Hermann Hesse that some of the band members were reading. It is a direct quote from this paragraph:

We stood before it and began to freeze inside from the exertion. We questioned the painting, berated it, made love to it, prayed to it: We called it mother, called it whore and slut, called it our beloved, called it Abraxas.”

And what artwork might fit such a reference? The perfect match was found in a painting by artist Mati Klarwein. In 1961 he created the wonderful and colorful painting and named it Annunciation. Carlos Santana noticed a reproduction of the painting in a magazine page and contacted the artist. The result became one of the most celebrated album covers of all time.

Santana was looking to up the sound quality of their albums a notch after their debut. While they loved their first effort, they did not consider it a high quality sounding album. For the second album they sought help to achieve that goal, and they looked no farther than sound engineer Fred Catero. His credits in the late 1960s spoke for themselves, among them Big Brother & The Holding Company – Cheap Thrills, Mike Bloomfield / Al Kooper / Steve Stills – Super Session, Blood, Sweat And Tears II and Chicago Transit Authority Volume 1. Santana asked him to produce Abraxas, and this was one of his very first producing jobs. Carlos Santana: “Fred helped make it easy for us to paint and play without worrying whether we were getting recorded in the right way.” The recording took place at Wally Heider’s recording studio in San Francisco, famous for recording many staple Bay Area bands including Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service and the Grateful Dead.

Abraxas was a critical album in the history of Latin Rock. Its commercial success, five million copies sold in the US, brought Santana’s flavor of Latin American rhythms to audiences who were not exposed to the likes of Tito Puente, Mongo Santamaria and other Latin music artists. Drummer Michael Shrieve discussed how he approached playing that style of music: “I remember when we first went to New York, went to Corso’s, the Latin dance club where Tito used to play, and that was a revelation. For me to figure out what to play with these percussionists – that was new for me. I didn’t play any Latin music. I mean, if anything, I was jazz and R&B. So kind of for me, it was just like, OK, how do you stay out of the way and just be a part of that rhythm, that groove? So anything I did, I did not play like Latin players whatsoever in Santana. I let them do that. My whole rhythm is swing on the cymbal, so I think that that combination was unique in itself – like, the way everybody played. It wasn’t New York players, you know?”

Another major accomplishment of the album was the fact that the band’s choice of cover songs, which they adapted exceptionally well to their music, earned the original songwriters handsome royalty payments. Carlos Santana: “Abraxas was very good to a few people who had songs we covered. They all got nice royalties for a long time, and I’m happy about that—Peter Green, Gábor Szabó, Tito Puente. Tito was always funny about it in the years after the album went big. He complained that people expected to hear our version of ‘Oye Como Va’ rather than his, and he had to deal with that. ‘People are always saying, ‘Why don’t you play it like Santana?’ First I want to get mad, and then I think, I just got a new house because of that. ‘Okay, no hay problema.’”

No article reviewing Abraxas can do without featuring its best known track and one of the most successful cover songs of all time. Carlos Santana remembers: “We started playing ‘Black Magic Woman’ early in 1970. It was a song by Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac that was a blues-rumba of the kind that Chicago blues guys would sometimes play. It was really Otis Rush’s ‘All Your Love (I Miss Loving)’ with different words. We brought up the Latin feel in Peter Green’s version, and when we played it live it made a great segue to Gábor Szabó’s ‘Gypsy Queen.’” Indeed when the band first started playing their version of the song, even before Abraxas or the single were released, the crowds went wild. It was a sure hit right from the first notes of the Hammond organ. Santana talked about Gregg Rolie’s critical contribution to the song: “He has a really, really powerful sense of knowing how to start a story—check out the opening of ‘Hope You’re Feeling Better’ or ‘Black Magic Woman.’ Santana likes dramatic openings, whether big or mysterious.”

The fantastic segue from Black Magic Woman to Gypsy Queen came about as a tribute to one of Carlos Santana’s musical heroes, guitarist Gábor Szabó. Carlos Santana talked about the first time he listened to the eclectic guitar player on Chico Hamilton’s album El Chico: “It was Gábor’s guitar that hit me hard—I heard that and could feel my brain molecules starting to expand. His sound had a spiritual dimension to it, and it opened the gates to other dimensions for me. You could tell he listened to a lot of Indian music, because he put a drone part in the music. It was trance music—he could play the simplest melody but still go deep. He was the first guitarist who opened me up to the idea of playing past the theme, of telling a story that isn’t just a regurgitation of the head of a song or other people’s licks. Gábor took me away from B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, and Jimmy Reed.” One of Gábor Szabó licks that Santana heard on Chico Hamilton’s albums became a key part ‘Soul Sacrifice’, the track that made the band world famous when they performed it at the Woodstock festival. Santana found it natural to play continuously after ‘Black Magic Woman’ and go directly into ‘Gypsy Queen’, a track from Gábor Szabó’s 1966 album Spellbinder.

Sources:

Fortunate Son, My Life, My Music, by John Fogerty

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light, by Carlos Santana

Categories: A Year in Music